Barth and Bonino

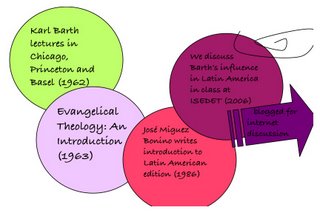

Over the past few weeks, our theological methods class has been reading Karl Barth's Evangelical Theology: An Introduction, and Dogmatics in Outline. As well as considering Barth's influences and political context, we've also discussed Barth's impact on liberation theologians such as Emilio Castro, Julio de Santa Ana, Gustavo Guiérrez and José Míguez Bonino.

In her book, The Praxis of Suffering Rebecca S. Chopp comments:

Latin American liberation theologians, trained in twentieth-century theology, retrieve the notions of freedom, grace, sin, obedience, and redemption as a way to interpret Christian praxis. In this hermeneutics of retrieval within modern theology, theological concepts are often radically transformed. For instance, Karl Barth's stress on obedience to the revelation of God comes to the surface in Jose Miguez Bonino's vision of theology as the discernment of God's actions in concrete situations...Latin American liberation theology continues modern theology's concern for the subject, the representation of freedom by Christianity, and the experience of faith in history but, in a radical reformulation, defines the subject as the poor, reinterprets freedom to include political self-determination, and envisions history as the arena for both liberation and redemption

(Chopp 1986: 45-6, Orbis Books Avaliable on Religion-Online)

As a native English speaker and European, it's easy to forget that readers in many countries wait years for editions to be published in their country or language (This month ISEDET is launching a translation of some of the texts of Swiss Reformer Zwingli from the 15th century; now that's a long wait!). The Spanish translation of Barth's Evangelical Theology: An Introduction was published in 1986 in Argentina (although many pastors and theologians would have been familar with the original German version published 1963).

The translation includes an Introduction by José Míguez Bonino, a Methodist theologian from Argentina. In his retirement, Bonino continues his association with ISEDET, and can often be seen chatting with students in the corridors or popping into a class. I have especially appreciated his interest in feminist studies, for example he attended most of the recent course on feminist theological anthropology. I note also that Marcella Althaus-Reid, includes him in her thanks in the preface to her book Indecent Theology (more on Marcella and her work in future blogs).

Bonino's introduction to Barth draws out Barth's social engagement, noting for example his early ministry amongst industrial workers and trade unions.

His social lens through which to view Barth is unsurprising considering the translation was published the same year as the military dictatorship ended (1976 - 1983, the so called Dirty War) following a period of great risk for the churches who committed themselves to the human rights struggle.

Bonino reflects Barth would have probably had some 'grave hesitations' with liberation theology but nevertheless, like Gutiérrez, sees 'fertile ground' within Barth's ideas. He offers three reminders for liberation theologians from Barth's work:

1.A call for modesty

That we do not take ourselves too seriously as 'liberation theologians'. As if we were the 'liberators'...As if the future of the poor depended on us. The only Liberator, Jesus Christ has the first word..He is the one who brings good news to the poor..The second word is the response of the community of faith. (21)

But, Bonino asks, does Barth's emphasis on the primary action of God disable human action? Not if we consider Barth's lifelong social action, culminating in the Barmen Declaration.

2.A call for committment

While God's will can never be directly identified with a political movement or group, Bonino reminds his readers that God's word and work can only be encountered in history. He points out Barth's focus on the covenant between God and humanity, our response to God's word.

3.A call from and for the poor

Bonino quotes Barth as saying God is always and unconditionally to be found alongside the humble (Dogmatics II/1, p.434). The word from heaven in the face of hell on earth (citing Gutiérrez).

4.A call to newness

Barth challenges us to be constantly open to the newness of God rather than stuck in our own system of theology.

The living Word of God, that points always to the new and the condition of the poor, that is known incompletely, broken and inaccessible in humanity...leaving open space for the creation of possibilities and projects - certainly human and therefore ambiguous and imperfect, but by such things, freely the power of the Spirit returns, forever and ever, to renew the face of the earth.(25)

(Introducción a la Teología Evangélica, (trad. E. de Delmonte) Buenos Aires: La Aurora 1983, my translations)

Comments